This Time it’s Personal: China Targets the Human Factor in Cyber-Influence Defense

- CRC

- Dec 16, 2025

- 8 min read

Background: The Xiamen Bounty

In October 2025, the Xiamen Public Security Bureau issued bounties for 18 officers from Taiwan’s Information, Communications and Electronic Force Command (ICEFCOM), accusing them of "inciting secession" and spreading disinformation. On November 13th, another bounty was issued, this time for information on two Taiwanese influencers, accused of disseminating ‘anti-China propaganda’.

Taipei has dismissed these acts as theatrical "crude cognitive warfare". However, these actions exemplify the increased prominence of a defensive technique being employed by nation-state actors: targeting human operators behind digital hostile influence campaigns (HICs) and offensive cyberattacks, as a countermeasure and deterrent.[i]

This is not the first case where China opted to target individuals involved in what it considered as hostile activities online. The counter-operator approach was already practiced in September 2024, when China’s Ministry of State Security (MSS) accused the hacker group "Anonymous 64" of conducting “cyber cognitive warfare” on behalf of ICEFCOM.

By doxxing three Taiwanese officials (releasing their names, photographs, and identification numbers) MSS signaled a clear intent to target personnel, whenever they could be identified.[iii]

Beijing’s use of personalized bounties and exposure, to individually target its perceived adversaries and critics online, extends beyond Taiwan. In March 2025 Global Affairs Canada (GAC) released a statement blaming the PRC for a multi-year online harassment campaign. The operation dubbed ‘Spamouflage’ involved the high volume (approx. 100 to 200 posts per day) use of deepfake and synthetic media, including sexually explicit images, to target Canadian residents deemed critical of the PRC.

Beijing’s strategic aims are designed to achieve three main objectives:

Deter future information operations (IOs): enforcing personal accountability on those involved in hostile hybrid and Soft Power activities against Chinese digital assets.

Degrade adversary capabilities: disrupting operational conduct by subjecting individuals to sanctions, potential demoralization, and exposure of covert personas.

Narrative control: positioning China as the victim of foreign aggression and influencing public opinion by framing online criticism of the PRC as conspiratorial and criminal.

The Counter-Cyfluence Toolkit

Historically, defense against information operations and hostile Cyfluence attacks focused on the technical, content, and narrative aspects of these hybrid threats. Defenders’ strategies typically involved reactive measures, such as:

Taking down offensive operational infrastructure (e.g. botnets, lookalike webpages, malicious domains, proliferation assets)

Countering hostile narratives (mainly through fact-checking and Strategic Communication)

Flagging manipulative content (e.g. engineered information disorder, coordinated synthetic propaganda) [v]

Deploying cyber security safeguards to block external attacks, identify malicious insiders, mitigate technical vulnerabilities and minimize risk of sensitive data leakage which could, in turn, feed HICs (i.e. hack-and-leak operations).

However, as state and non-state actors increasingly utilize HICs and hybrid operations to achieve geopolitical objectives, and as alternative remediation and deterrence measures have proven to be of limited effectiveness, nation-state actors are increasingly incorporating a new response strategy into their counter-cyfluence playbook: Counter-Operator actions.

By identifying and pressuring the individuals behind offensive kill-chains, defenders aim to achieve an accumulated advantage via personalized effects: "burning" operator cover, freezing assets, restricting movement, and applying mounting psychological stress. These consequences are designed to alter the risk calculus for key individuals and create operational challenges for adversaries.

The U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) has explicitly framed this as a strategy to “end the impunity that then reigned in cyberspace” by “publicly deploying its unique tools... to disrupt and deter state-sponsored cyber threats”. [vi]

A Multi-Layered Approach

Common methods of Counter-Operator action applied by state actors include:

Legal strategies - utilizing indictments, travel bans, and "lawfare" to threaten incarceration and restrict global mobility.

Economic measures - involving targeting individuals with sanctions, asset freezes, and transaction restrictions.

Diplomatic efforts - leveraging "naming and shaming" to strip away anonymity, shape global perception, and impose reputational costs.

Extra-judicial tactics - operating in the “gray zone”, using doxxing and intimidation, including the implied or actual threat of physical harm.[vii] [viii]

Extending Actor Attribution

Crucially, operator-targeting relies on accurate attribution. The NATO StratCom Center of Excellence's "IIO Attribution Framework" offers a relevant model, suggesting that attribution requires fusing three types of evidence: Technical (digital traces like IPs and malware); Behavioral (actor TTPs); and Contextual (narrative, linguistic, and socio-political analysis).

Bridging the attribution gap from state or organizational level identification, and individual responsibility demands significant intelligence and operational resources. Individual attribution often relies on private-sector proprietary data, such as customer records or platform-specific telemetry, that is not publicly available. Even then, granular attribution often still requires the leveraging of classified intelligence and capabilities.

This creates a cost-effectiveness dilemma for state actors: attribution risks exposing defender TT&Ps and the extent of penetration of adversarial organizations and expends more operational capacity.

A Global Trend

Despite their operational costs, China is not alone in deploying people-centric countermeasures. Commentators have noted that Beijing’s adoption of public attribution and doxxing tactics mirrors the "naming and shaming" long employed by Western nations and organizations against offensive cyber activities (including Chinese operations).[x]

United States

Washington has systematically employed the Department of Justice (DOJ) and Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) against hostile actors. Executive Order 13848 explicitly permits sanctions against "any person" found to have "directly or indirectly engaged in" election interference.

Notable applications involve the 2018 indictment against Yevgeniy Prigozhin, then head of the Russian “Internet Research Agency” (IRA), who was heavily sanctioned along with individual IRA employees for ‘foreign interference in the United States’.

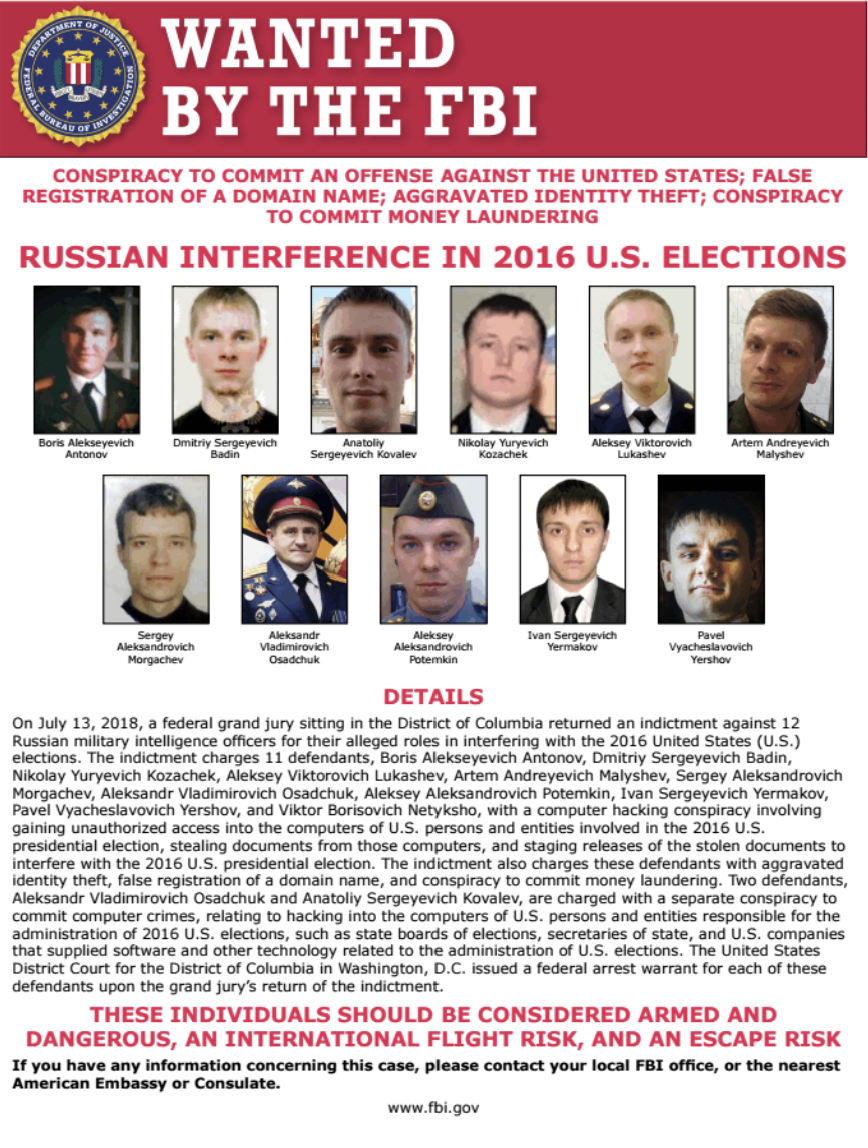

And the September 2024 indictment of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) targeted individual operators such as Masoud Jalili and extended to individual subcontracted employees for their role in Cyfluence operations, including hack-and-leak attacks targeting the US elections [xi].

Figure 5 - FBI Wanted posters showing indicted Iranian and Russian individuals. [xii]

European Union

Since 2014 The EUs defensive posture has become notably more proactive, largely in response to the intensification of foreign information manipulation and interference (FIMI) against member states.

The bloc has launched numerous initiatives, like the FIMI Toolbox and enacted legislation, such as EU Regulation 2023/888 which explicitly penalizes individuals for ‘the dissemination of disinformation’. [xiii]

The EUs use of sanctions in response to FIMI has become more personalized, previously its sanctioning regimes were aimed at typically state-level actors however, there has been a distinct towards ‘smart sanctions’ aimed at specific individuals or entities. [xiv]

As an additional financial lever, in early 2022, the EU has established the “Freeze and Seize Task Force” to target individuals, including those responsible for cyber-attacks and FIMI actions. As of October 23, 2025, over 2,500 individuals and entities have been sanctioned, and more than €28 billion in private assets frozen.[xv]

Ukraine and Russia

The early stages of the Russia-Ukraine war saw rapid developments in Information Warfare tactics, including the use of counter operator targeting.

Notable is the use of extra-judicial methods such as the Ukrainian "Myrotvorets" (Peacemaker) list. Proclaiming to be “an independent non-governmental organization”, it maintains a database of individuals accused of being enemies of Ukraine, including "Kremlin propagandists" and information operatives. [xvi]

In essence, the platform serves as an open-source registry designed to expose identities, impose personal costs, and intimidate listed individuals. Critics argue it represents a "hit list" that endangers and harasses people without due process and has been used to suppress journalism and authentic criticism of the Ukrainian government.

Although speculative in nature, the database’s association with physical violence and homicide has created a reputation that highlights the deterrent potential of targeted doxxing and psychological threats.[xvii]

Russia has established a comparable database named ‘Project Nemesis’, which serves a similar function. [xviii]

Conclusion

Fundamentally, targeting the human element behind information operations is not a new concept in state-level confrontation; espionage and kinetic defense have always involved neutralizing key personnel. The increased prominence of counter operator targeting as a defensive tactic merely underscores the impactful role that hybrid influence operations now play in state level geopolitical conflict.

As a proactive counter-influence methodology, counter operator targeting can complement, but not replace, existing cognitive, technical and content-based countermeasures.

Its effectiveness is contingent on the ability to apply tangible costs to an individual. If the target is sufficiently insulated from the consequences, or the defender lacks sufficient legal, economic, or diplomatic clout to inflict damage, then operator targeting could prove counter-productive by providing an adversary with a propaganda victory and exposing the defenders’ TTPs and intelligence assets.

And while evidence suggests that targeting individuals can disrupt operations, it does not constitute complete remediation. For example, GRU Unit 26165 (Fancy Bear) remains operationally active despite repeated targeting of its members with sanctions, indictments, and exposure.

Ultimately, the value of this tactic extends beyond threat neutralization. By tactically altering an individual's risk calculus through the application of personalized costs, a defender can transfer these costs on a strategic level to their adversary.

[Footnotes:]

[i] The Independent, S. Sharma, China issues bounty for 18 officers in Taiwan’s ‘psychological warfare unit’. [online] Published 11 October 2025. Available at: https://www.independent.co.uk/asia/china/china-bounty-taiwan-military-psychological-warfare-b2843641.html

[ii] China News (中国新闻网), Post on Facebook (Reel). [online] Available at: https://www.facebook.com/reel/1189876776392002

[iii] Jamestown Foundation, S.-F. Lee, China Brief Volume 25 Issue 14. Taiwan Bounty: PRC Cross-Agency Operations Target Taiwanese Military Personnel. [online] Published 25 July 2025. Available at: https://jamestown.org/taiwan-bounty-prc-cross-agency-operations-target-taiwanese-military-personnel/

[iv] CCTV, citing Ministry of State Security, Doxxing “Taiwan independence” network army ‘Anonymous 64’. [online] Published 23 September 2024. Available at: https://news.cctv.com/2024/09/23/ARTIvJFrhmdCf4SdWR1yVfVH240923.shtml

[v] EEAS, 2nd EEAS Report on Foreign Information Manipulation and Interference Threats: A Framework for Networked Defence. [online] Published January 2024. Available at: https://www.eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/2024/EEAS-2nd-Report%20on%20FIMI%20Threats-January-2024_0.pdf

[vi] Royal United Services Institute (RUSI), RUSI Panel Explores Role of ‘Naming and Shaming’ as a Tool of Cyber Statecraft. [online] Published 5 December 2024. Available at: https://www.rusi.org/news-and-comment/rusi-news/rusi-panel-explores-role-naming-and-shaming-tool-cyber-statecraft

[vii] Lawfare, G. Band, Sanctions as a Surgical Tool Against Online Foreign Influence. [online] Published 15 September 2022. Available at: https://www.lawfaremedia.org/article/sanctions-surgical-tool-against-online-foreign-influence

[viii] U.S. Department of the Treasury, Treasury Sanctions Russians Bankrolling Putin and Russia-Backed Influence Actors. [online] Published 3 March 2022. Available at: https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy0628

[ix] Psychological Defense Research Institute (Lund University), ADAC.io project, A Framework for Attribution of Information Influence Operations. [online] Published 2025. Available at: https://www.psychologicaldefence.lu.se/sites/psychologicaldefence.lu.se/files/2025-02/250131_ADACio%20D1.1_Attribution%20Framework%20Report_Final.pdf

[x] Binding Hook, B. Read, China is using cyber attribution to pressure Taiwan. [online] Published 22 July 2025. Available at: https://bindinghook.com/china-is-using-cyber-attribution-to-pressure-taiwan/

[xi] US Dept of Justice, Three IRGC Cyber Actors Indicted for ‘Hack-and-Leak’ Operation Designed to Influence the 2024 U.S. Presidential Election. September 27, 2024. Available online:

[xii] Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) Most Wanted, three Iranian cyber actors. [online] Published 27 September 2024. Available at: https://www.fbi.gov/wanted/cyber/three-iranian-cyber-actors/; FBI, Most Wanted, Russian Interference in 2016 U.S. Elections. [online] Published July 2018. Available at: https://www.fbi.gov/wanted/cyber/russian-interference-in-2016-u-s-elections

[xiii] Council of the European Union, Council Implementing Regulation (EU) 2023/888 . [online] Published 30 May 2023. Available at: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32023R1045&qid=1765546232156

[xiv] https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2021/656323/EPRS_STU(2021)656323_EN.pdf European Parliamentary Research Service (EPRS), Strategic communications as a key factor in countering hybrid threats. [online] Published 2021. Available at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2021/656323/EPRS_STU(2021)656323_EN.pdf

[xv] European Commission, Sanctions against individuals, companies and organisations. [online] Published 3 October 2025. Available at: https://commission.europa.eu/topics/eu-solidarity-ukraine/eu-sanctions-against-russia-following-invasion-ukraine/sanctions-against-individuals-companies-and-organisations_en

[xvi] DFRLab (Medium), UN Calls for Investigation of Ukrainian Digital Blacklist. [online] Published 21 September 2017. Available at: https://medium.com/dfrlab/un-calls-for-investigation-of-ukrainian-digital-blacklist-14fec836753f

[xvii] Factcheck, M. Kirkova, Is the Myrotvorets website a hit list. [online] Published 1 November 2023. Available at: https://factcheck.bg/en/is-the-myrotvorets-website-a-hit-list/

[xviii] Institute for Strategic Dialogue, Project Nemesis, Doxxing and the New Frontier of Informational Warfare Available at: https://www.isdglobal.org/digital_dispatches/project-nemesis-and-the-new-frontiers-of-informational-warfare/

[xix] The "Peacemaker"(Myrotvorets) Center, last accessed 08/12/25 Available at: https://myrotvorets.center/criminal/

[xx] U.S. Department of the Treasury, Treasury Sanctions Russians Bankrolling Putin and Russia-Backed Influence Actors. [online] Published 3 March 2022. Available at: https://home.treasury.gov/news/press-releases/jy0628

_edited.png)

.png)